The site of the sanctuary in Metapontion dedicated to Apollo and Aristeas, described by Herodotos and in a story retold by Athenaios, was uncovered during excavations in the 1980s and confidently identified thanks to the recovery from the site of a large number of votive bronze laurel leaves, a typical feature of Apollo worship among ancient Greek colonists of southern Italy. According to the ancient writers, the sanctuary was set up because Aristeas commanded it during a supernatural visit to the city centuries after his natural life.

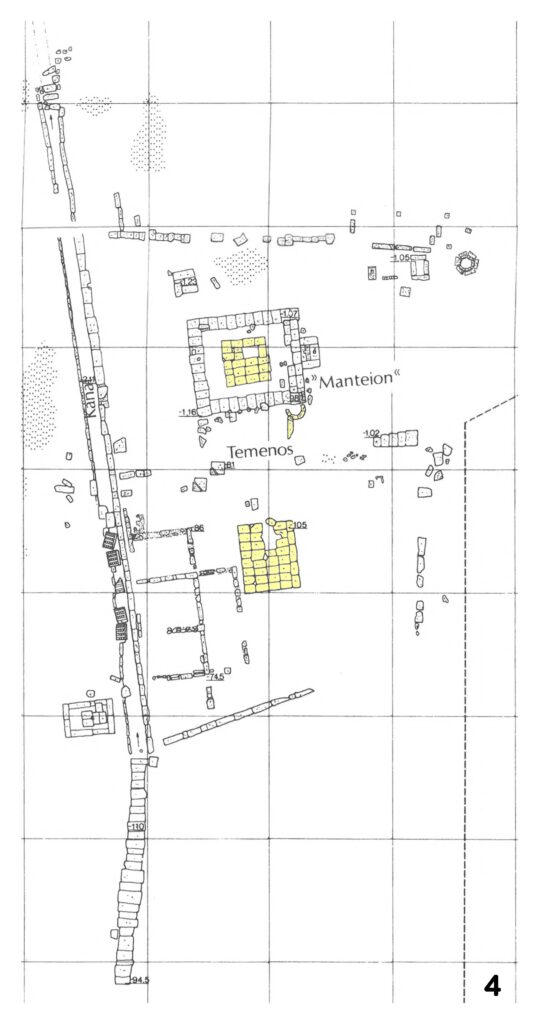

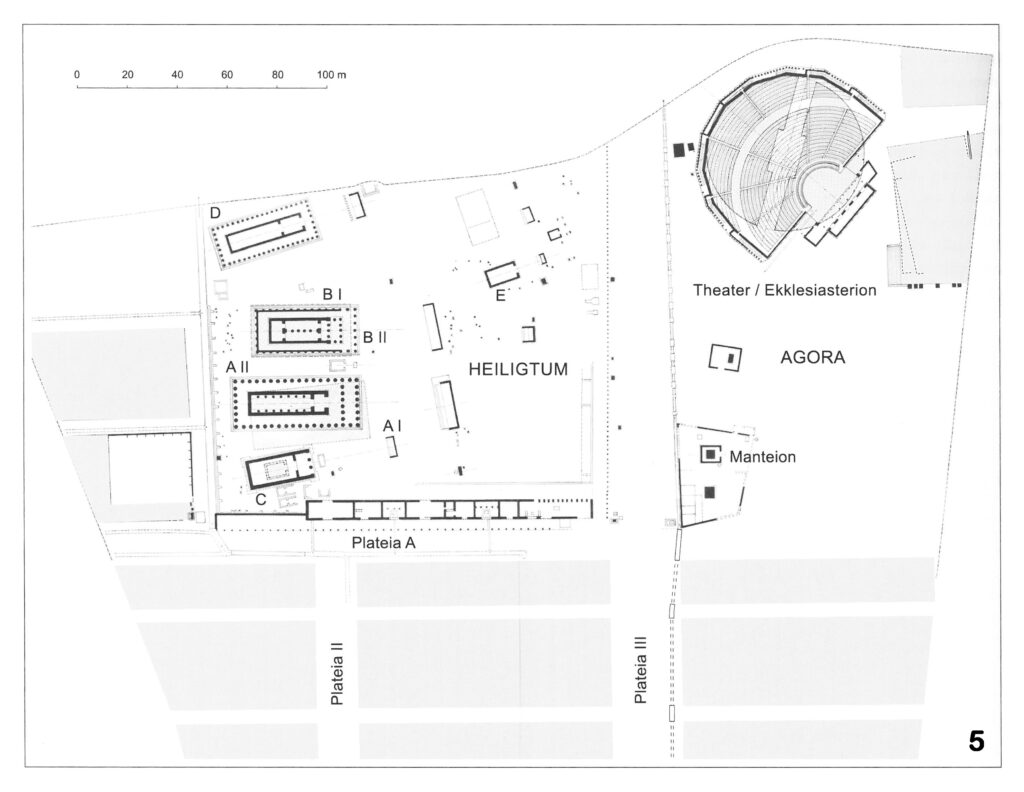

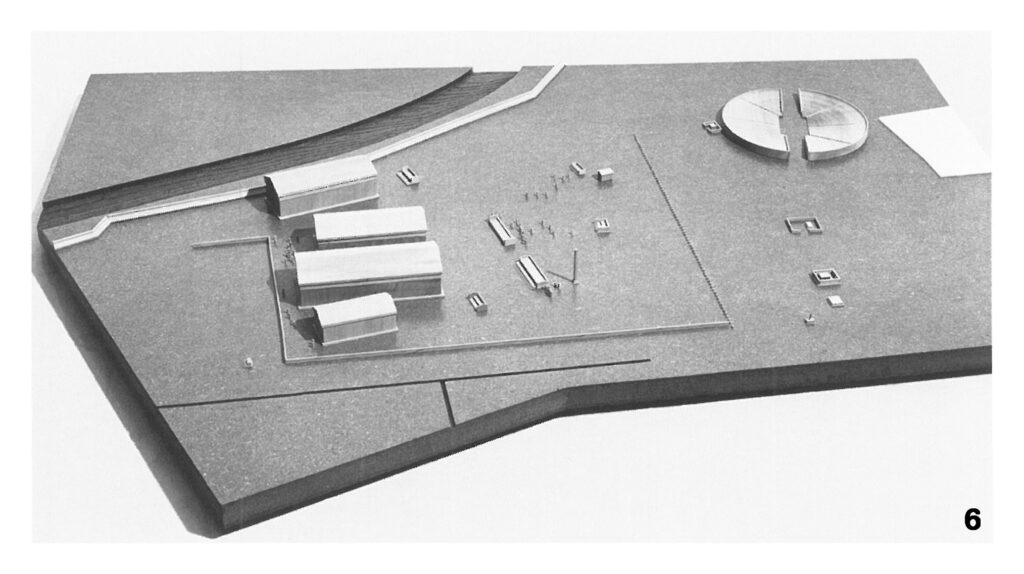

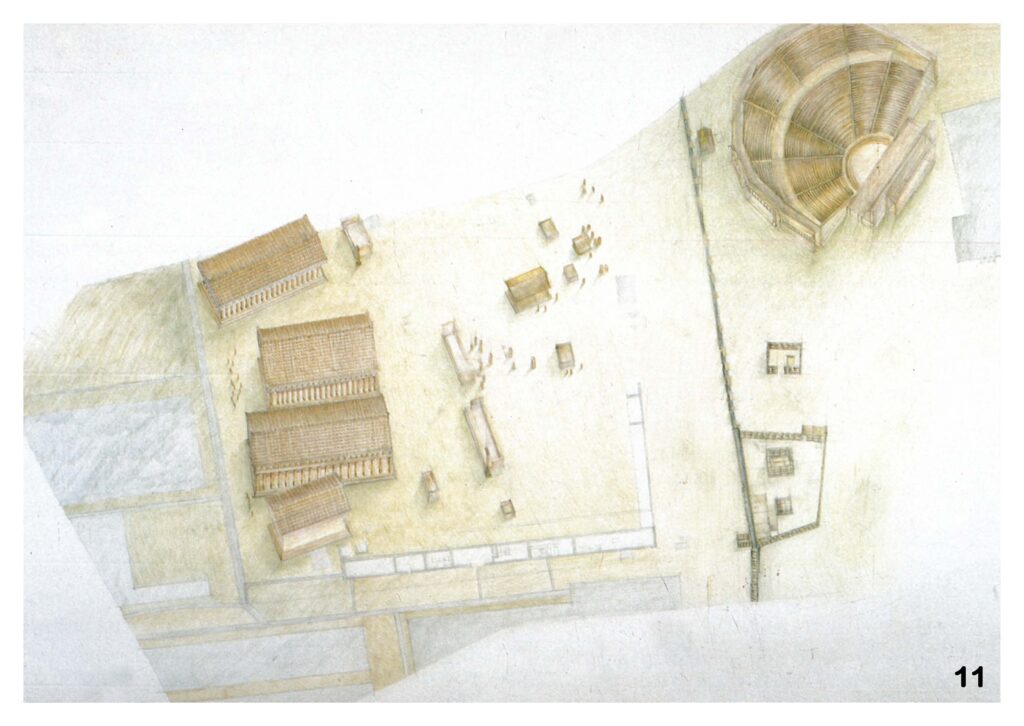

The oldest structures on the site have been dated to the early 5th century BCE, and consist mainly of two stone platforms, about 11 meters apart and aligned on a north-northeast axis (image 1, with southern platform in left foreground and northern platform partly visible at right; image 4, with 5th century BCE structures shaded yellow; and image 7, with southern platform in foreground). Also surviving from the sanctuary’s earliest period, near the southeast corner of the northern platform, is a remnant of a circular stone wellhead and a short segment of wall foundation extending south from the wellhead (image 3, foreground). The sanctuary, also called a temenos (sacred precinct), was within the central market area or agora of Metapontion (image 5), southeast of the city’s temple district (marked Heiligtum on image 5) and southwest of the ekklesiasterion (public assembly building, later replaced by a theater).

Since the bronze laurel leaves were found in the area of the northern platform and wellhead, Antonio De Siena in his excavation report (Metaponto Scoperte, §1.3) proposed that the well and leaves served Apollo worship rituals that were carried out specifically in that area. And since the story retold by Athenaios mentions diviners present at the sanctuary, this northern platform is thought to have had an oracular function and is often referred as a manteion (oracle). Based on evidence from other nearby sanctuaries, the leaves are believed to have been attached to bronze reproductions of laurel branches and brought to the sanctuary as votives. Wells have been associated with oracular Apollo sanctuaries elsewhere, most prominently at Didyma near Miletos (Weber, Apollon von Didyma, 27). In Athens a well with an inscription seeking an oracle from Apollo was recently discovered (Stroszek, Wells in Athens, 46; Archaeology and Arts, Apollo in Athens). In south Italy, the sanctuary of Monte Papalucio is suspected to have included a well or spring and its location is suspected to have been related to groundwater supply (Mastronuzzi, Monte Papalucio, 31 and 224).

De Siena also proposed (op. cit.) that the wellhead and fragment of wall foundation near the northern platform (image 3, foreground) belonged to an otherwise completely destroyed building, which was replaced in the late 3rd century BCE with a square building that surrounded and enclosed the northern platform. The foundations of the later building are still present at the site today (image 5 and image 2, uncolored square structure). Unfortunately it’s impossible to know what the Classical-period structure that stood by or around the northern platform looked like, or how much larger it was than its meager extant remains. A three-dimensional model of central Metapontion of the early Classical period by Dieter Mertens represents the Apollo sanctuary’s northern platform surrounded by an unroofed rectangular enclosure (image 6, lower right), apparently relying on an assumption that the Classical-period structure was similar to the building that replaced it in the 3rd century BCE.

While the northern platform is roughly square and slightly less than 4 meters on each side, the southern platform (image 1, left foreground) is a larger rectangle of about 5.6m by 4.6m. The southern platform’s outer stones were also fastened to each other with lead-soldered iron clamps, indicating that it supported considerable weight (De Siena, op. cit. with n. 42; on such clamps see Scappin, L’impiego del Metallo).

According to Herodotos, the sanctuary was surrounded by laurel trees and included statues of Apollo and Aristeas that stood next to each other. The story retold by Athenaios adds that the sanctuary included a bronze laurel. There is also a depiction of a statue of Apollo on Metapontine silver coins, which from the coins’ 5th century BCE dates, and from the large laurel branch that the statue is shown holding, can be identified as the statue that stood in the market sanctuary.

De Siena (op. cit.) proposed the following reconstruction of the sanctuary’s arrangement: the south platform supported the statue of Apollo and a stone stele; the north platform supported the sanctuary’s altar to Apollo; the building that incorporated the well-head surrounded the north platform with an entrance on its eastern side; and the bronze laurel mentioned by Athenaios referred to a bronze reproduction of a laurel tree that stood at that eastern entrance and was the focus of the ritual involving the bronze laurel leaves. This reconstruction implies that Aristeas’ statue also stood on the southern platform (image 1, left foreground).

This reconstruction still seems to be the most convincing, with the exception of De Siena’s grounds for locating the bronze laurel tree, which is based on a feature of the square building surrounding the north platform built in the late 3rd century BCE. One of the basement stones of the entryway of that building’s eastern side has a hole drilled vertically through it (image 3, upper right), which De Siena proposed was used to fix the trunk of the bronze laurel tree into the entryway floor. But it seems very impractical to put a bronze laurel tree in that location, as the votive bronze branches with attached bronze leaves that are believed to have been attached so that they radiate out from the tree would get in the way of entering and exiting the building. Also there is a semicircular remainder of a second hole visible in a second entryway basement stone (image 3, upper right), which suggests some different purpose that required two holes in the entryway floor. It seems better to locate the bronze tree only very generally in the area of the north platform, as the textual evidence for its existence refers to the Classical period and the extant remains of the building around the platform are later and don’t convincingly suggest any location for a bronze laurel tree.

Others have suggested that the bronze laurel mentioned in the Athenaios story was the large laurel branch held by the Apollo statue depiction on coins (Stazio, Monetazione di Metaponto, 83; Carter, Countryside at Metaponto, 217), or that the Apollo statue stood on the northern platform and its laurel branch was the focus of the ritual in which votive bronze laurel leaves were brought to the sanctuary (Hernández Castro, El Temenos). The problem with these suggestions is that the northern platform seems small to accommodate both a statue of Apollo and an altar, let alone a second statue of Aristeas. Hernández Castro’s suggestion (op. cit.) that the bigger southern platform supported the statue of Aristeas while Apollo stood on the smaller northern platform (which was possibly already enclosed in the Classical period) perhaps shouldn’t be ruled out but seems less likely, as one would expect the god and not Aristeas to be the sanctuary’s central image.

Hernández Castro (op. cit.) also drew attention to the alignment of the sanctuary’s northern platform with the central aisle of the ekklesiasterion (image 5), and argued that this alignment was deliberate and showed that the sanctuary was connected to public festival activities held at the ekklesiasterion. He argued that the Apollo sanctuary, along with another shrine between it and the ekklesiasterion and shrine to Zeus just west of the ekklesiasterion, should be considered part of the ekklesiasterion’s territory, although the two texts that mention the sanctuary refer to it as located within the market.

The late 3rd century BCE, when the sanctuary site underwent a number of additions and renovations, was a time of tumult for Metapontion, which was aligned with Hannibal of Carthage before it was conquered by Rome. The square shrine building surrounding the northern platform was initially built with only three sides, and ‘very probably’ a balustrade protecting its eastern side, later replaced by a fourth wall, with an entryway in the middle (De Siena, op. cit.). The shrine had high walls, with fragments of a Doric frieze with triglyphs and metopes found in the area, but was roofless. Also a wall was built around the entire sanctuary area, and in the 2nd century BCE another building with several rooms was added in the southwest corner of the sanctuary, which De Siena suggests was a hestiatorion for ceremonial banquets (op. cit.; Metaponto e il Metapontino, 116). Whether other elements of the sanctuary changed, such as the statues and bronze laurel, is unknown. It is this later version of the sanctuary that is reflected in the extant remains (images 2, 4-5 and 7-11).

One of the main mysteries about the Metapontine market sanctuary is whether its appearance in the 5th century BCE was related to the Pythagorean movement. The matter is complicated by the generally poor quality of sources on this period of southern Italy’s history: the earliest known histories of the region were written in the mid-4th to early 3rd centuries BCE, and only fragments of them survive. According to these, Pythagoras moved in the late 6th century BCE from the island of Samos to the city of Kroton (modern Crotone), about 150km south by sea from Metapontion, and after developing a large following in Kroton, Pythagoras and his followers were attacked by a political rival and scattered, while Pythagoras fled to Metapontion and died there (Huffman, Pythagoras). Pythagoras is estimated to have died in around 490 BCE, very close to the time that the Metapontine market sanctuary to Apollo was created.

The surviving accounts say little about a Pythagorean community of Metapontion, but a 4th century CE history of early Pythagoreanism listed the names of 38 prominent Pythagoreans from Metapontion (Iamblichos, 36/267), a greater number than he recorded for Kroton. That list of Metapontine Pythagoreans even included Aristeas, which suggests that one of Iamblichos’ sources on early Pythagoreanism knew the story of Aristeas’ purported visit to Metapontion and considered it to be related to the development of a Pythagorean community. Iamblichos also mentioned that ‘all Pythagoreans alike have trust in […] the mythologizing about Aristeas’. However Iamblichos did not mention Aristeas’ purported visit to Metapontion or the Metapontine market sanctuary, and neither Herodotos’ nor Athenaios’ stories about Aristeas and the Metapontine sanctuary say anything about Pythagoreans. Thus it appears that by the 4th century BCE, when the history of early Pythagoreanism began to be written, the Metapontines’ reverence for Aristeas was understood to be connected to Pythagoreanism. But whether Pythagoreans were actually involved in creating the sanctuary that honored Aristeas, or especially involved in its patronage, seems very uncertain.

Date of Work: c. 490 BCE

Source of Date of Work: De Siena, Metaponto Scoperte, §1.3

Key to images:

1. Apollo sanctuary of the Metapontion market, viewed from the south, with the southern platform where statues of Apollo and Aristeas likely stood at left foreground. De Siena, Metaponto Scoperte, fig. 12.

2. Northern platform of Apollo sanctuary of the Metapontion market, surrounded by remains of a 3rd century BCE shrine building, viewed from the east. Ibid., fig. 10.

3. Remains of a 5th century BCE wellhead and wall (foreground) next to the remains of the 3rd century BCE shrine building. Ibid., fig. 11.

4. Plan of the Apollo sanctuary of the Metapontion market, with 5th century BCE structures shaded yellow. Excerpted from Mertens, Metapont Plan, abb. 1a; shading added.

5. Illustration of central Metapontion. Mertens, Städte und Bauten, 156 abb. 270.

6. Model of central Metapontion in the 5th century BCE. Ibid., 159 abb. 275.

7. Remains of the Apollo sanctuary of the Metapontion market (foreground), viewed from the south. Ibid., 436 abb. 750.

8. Remains of central Metapontion, aerial view from the west. Ibid., 158 abb. 273.

9. Remains of central Metapontion, aerial view from the east. De Siena, Metaponto Archeologia, cover.

10. Remains of central Metapontion, aerial view from the south. Ibid., 23 fig. 15.

11. Illustration of central Metapontion with market Apollo sanctuary (lower right) as it appeared in the 2nd-1st century BCE. Ibid., front matter.